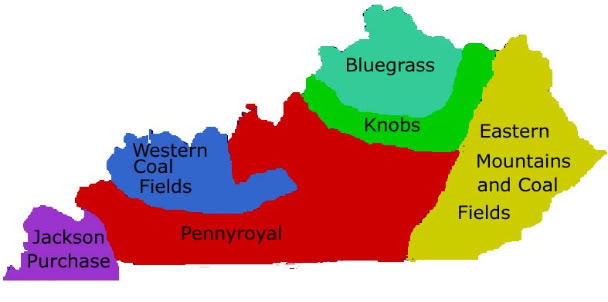

Two summers ago, I spent a month in the Kentucky Knobs without a map.

The Knobs horseshoe around the Bluegrass just south of the state’s northernmost tip. Unlike those gentle rolls, the Knobs are a ring of hills, or monadnocks. I was staying in a farmhouse near the peak of one knob.

The roads through the Knobs are like England’s lanes, a single-car width and twisting around blind curves and into hollows with only brief midday sunlight. Google was fine at getting me A to B. I wanted to explore with more planning.

I stopped at a gas station to buy a paper map. No maps.

Three more gas stations and three more shrugs.

“People have their phones,” a clerk told me.

“People have their phones,” a clerk told me.

One moonless night, I drove a winding route bolded on my phone. The headlight beams were thick with grasshoppers. Around one turn, I screeched to a halt.

A mother cat and her kittens huddled in the center of the asphalt to soak up the lingering warmth. I parked, moved them, the sky above brilliant with stars

Not knowing anything but that bolded route had its pleasures. I was constantly surprised: a beautiful, well-kept church, a colorful barn quilt emblem, a vista with the knobs rising like green islands above mist.

Yet I kept wondering: what am I missing? Where exactly am I in relation to a town or a river crossing?

I thought about that summer recently, when I read a listserv message by a Durham neighbor, Mira Sanderson. The message was angry.

“Less than an hour ago,” Sanderson wrote, “my boyfriend was followed by a police officer, who was called by one of my neighbors that reported a ‘suspicious looking car.’ Unfortunately, this hasn’t been the first incident in which my boyfriend has been called ‘suspicious.’ We have caught a few of my neighbors taking pictures of his license plate, and staring at him while he’s waiting in his car for me to come home.”

The boyfriend is black. “He’s a student athlete and an incredibly hard worker,” she continued. “Stop racially profiling him. I am disgusted to know that the person who called the police was someone from my own neighborhood, one of which continuously preaches liberalism and pro-black lives matter, advocating equality and safety for everyone, and has repeatedly seen my boyfriend and his blue Mazda at my house for the past 2 years.”

Patricia Harris, also a neighbor, responded with her own story, building on a letter she published in this newspaper. “I get stares and questioning looks from passers-by unless I’m talking with one of my old neighbors. I guess a 65-plus black woman handling a ladder must be a sight to behold, eh? Actually, I now live in one of Durham’s other more recently gentrified neighborhoods and have for 16 years yet I was followed by the police on a sunset walk not two months ago.”

In other words, long-time neighbors are being written out of our story, pushed literally off our common maps. Like Harris, they’ve spent their lives in Durham. Yet in our current political climate and paired with rapid gentrification, we’re creating a world where people of color are being made “suspicious” and strangers.

“Fear” is a political strategy meant to divide us and make what is familiar newly threatening. It’s not just what’s on the news; the fear is creeping up our doorsteps and into our hearts. It’s creeping into the hearts and minds of people who otherwise think of themselves as tolerant and welcoming. I have to say: we aren’t acting so tolerant these days.

This isn’t something new. The use of fear to divide people has a long and terrible history in the United States, in North Carolina and in Durham.

But this is a fear in our time. This is a fear that’s distorting the way we see and talk to each other in the most average of circumstances: the grocery store, the park, the curb in front of a teen’s home.

That doesn’t make it less awful. The dailyness of this fear makes it more awful, since fear can bust out at any moment, with potentially devastating consequences.

What if that fearful neighbor had called a police officer too quick on the trigger? Examples of this very scenario abound. What if someone with a gun decided to take matters to hand, as is also common? For so many of our neighbors, the potential consequences of fear, especially white fear, are fatal.

This isn’t a problem we can solve through legislation. Thankfully, I think. We have to solve it in our own hearts, first by acknowledging it’s there — and calling it out. Start conversations. Lend a hand. Listen. Powerful people want us to walk maps constrained by fear and suspicion. Refuse.

Published on June 15, 2018, in the Durham Herald-Sun