Sometimes, a newspaper article can have surprising repercussions.

Last fall, I ignored the spate of coverage of a self-help idea called “Swedish Death Cleaning.” As I now know, Swedish author Margareta Magnusson advised the middle-aged to de-clutter their lives so their families don’t have to muck out their living space after they die.

This is a more morbid take on the other de-cluttering guru, Marie Kondo, who urges us to toss whatever fails to give us joy.

“Cut your kids a break,” Magnusson seems to be saying, “and you never really liked that lamp anyway.”

My stepmother — who has a large house filled with stuff and a large basement even fuller with stuff — has taken to Swedish Death Cleaning with a passion. She’s quite healthy and in no danger of an imminent departure. But the task has made her almost giddy with delight, like a backpacker lightening the load on the last rocky climb.

So far, I’ve received my dad’s rifle (subject of a previous column), a porcelain whiskey container with Irish images (my dad used to fill the bottles of the expensive brands he received as gifts with the cheap stuff) and my dad’s pilot license. These are all things I’d known about when he was still alive.

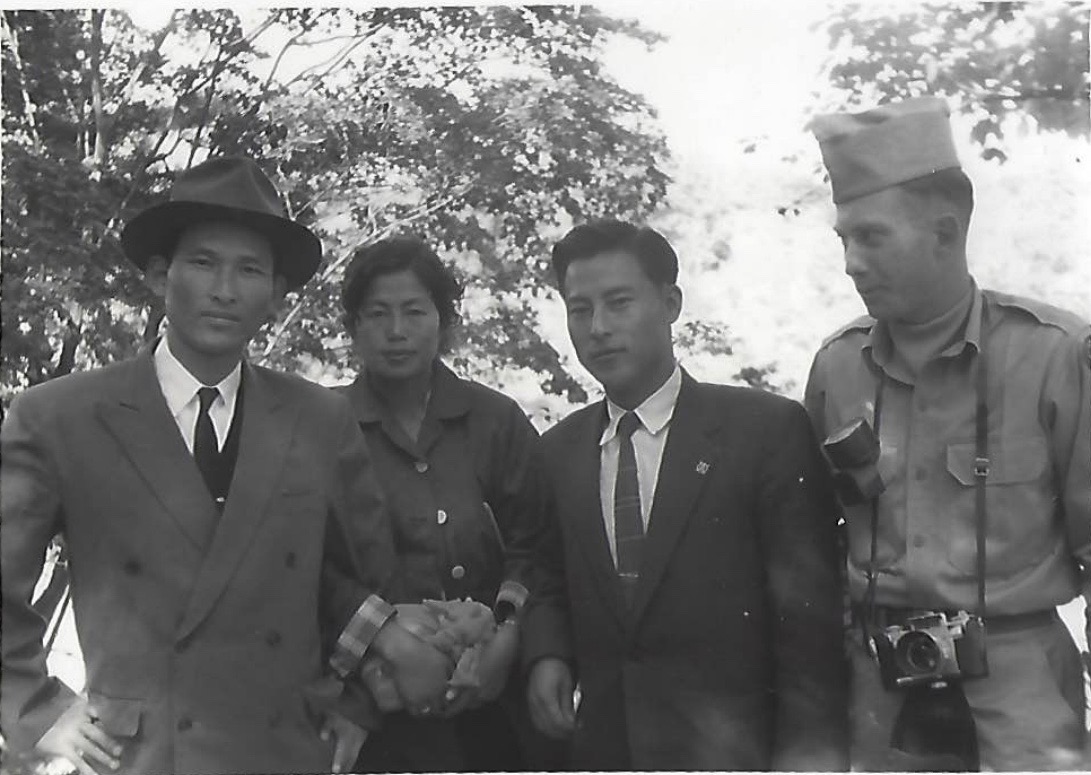

But last Thanksgiving, my stepmother surprised me with a stack of black and white photographs my dad took while stationed in Korea with the U.S. Army.

My dad wanted to be a Navy pilot, but failed the vision test (near-sighted with astigmatism, which I share). Once the discharge went through, the army drafted him and sent him to Korea to be a payroll clerk. The war — or “police action,” as it’s sometimes known — had ended, but US troops remain deployed there to this day.

The photos reminded me that when he was drafted, he’d already been shunned by his family for violating their conscientious-objector beliefs. He left their southern Illinois home literally with a satchel and the clothes on his back. After some adventures, he ended up at the little college when he met and married my mother. Then it was Korea.

As the photographer, he doesn’t appear in any of the photographs. A few show people — army buddies and some wonderfully fashionable Koreans, in sharp suits and hats. Overall, though, the photos are bleak — landscapes emptied of people.

My dad never showed us these photos. He hated the army and, it seems, everything about the world events that forced him to Korea.

One thing Swedish Death Cleaning has left me with is questions: about where these photos were taken, who these people were, if my dad every toyed with the idea of becoming a photographer. I wish I could ask, but my dad died more than a decade ago.

Most of the things I want to get rid of (and yes, I’ve started a bit of SDC, too) have no meaning. The extra Vornado heater, the too-baggy sweater, the superfluous wooden spoon.

Other things I can’t bear to part with. There’s the tongue-in-cheek California license plate (for a Fiat, it serendipitously had the word LUX, together referring to Fiat Lux, the motto of the University of California). Spools from a long-defunct Durham textile mill. The kids’ drawings.

When my mother moved to a retirement community, she was remarkably sanguine about ditching many of her belongings. But she surprised me the other day when she confessed that she’d been crying as she looked at some photographs. The images didn’t bring her joy; they made her sad, for the loved ones she’d lost, the tragedies she’d endured. But I’m certain she won’t get rid of them. Even if she never looks at the photographs again, they are precious to her.