(from the April issue of Sojourners)

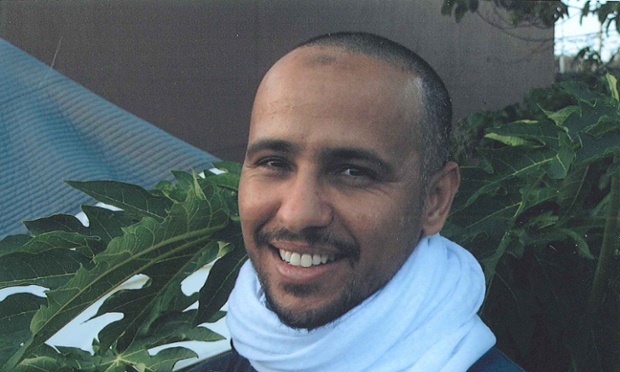

There’s no better sequel to the Senate Select Intelligence Committee‘s executive summary of the torture report than Mohamedou Ould Slahi‘s just-published Guantánamo Diary (Little, Brown and Company). This harrowing tale is but one of what will someday be many direct accounts by victims.

There’s no better sequel to the Senate Select Intelligence Committee‘s executive summary of the torture report than Mohamedou Ould Slahi‘s just-published Guantánamo Diary (Little, Brown and Company). This harrowing tale is but one of what will someday be many direct accounts by victims.

Originally from Mauritius, Slahi, 45, was detained on a journey home in January 2000 and questioned about the so-called Millennium plot to bomb the Los Angeles airport. Slahi admitted that he’d fought against Afghanistan’s communist government with the mujahedin, at that time supported by the US. But he never opposed the United States. Authorities released him. A year later, the young engineer was again detained and again released.

Months later, Slahi drove himself to a local police station to answer questions. This time, Americans forced him onto a CIA plane bound for Jordan, where he claims he was tortured. On August 5, 2002, Americans brought him to Guantánamo. Slahi is among the detainees whose horrific torture there is the centerpiece of the Senate report. None other than then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld signed the “special interrogation plan” authorizing his brutal ordeal.

Slahi divides his imprisonment into pre-torture, when he truthfully denied any involvement in terrorism; and post-torture, “where my brake broke loose. I yessed every accusation my interrogators made. I even wrote the infamous confession about me planning to hit the CN tower in Toronto, based on SSG [redacted] advice. I just wanted to get the monkeys off my back.”

His captors beat and threatened him, subjected him to bitter cold and sleep deprivation, stress positions and repulsive sexual abuse by female interrogators. Yet with astonishing grace, Slahi seems more traumatized by the torture he witnessed. He saw teenagers who could barely lift their heads, confused old men and others like him who said anything to get the pain to stop.

Slahi taught himself English so he could write his 466-page memoir, long kept secret. Once his lawyers got his manuscript released, authorities refused to let Slahi’s editor, journalist Larry Siems, meet him.

Siems calls the memoir “a journey through the darkest regions of the United States’ post-9/11 detention and interrogation program.” Far from regretting the darkness, torture’s most adamant defender, former vice president Dick Cheney, vehemently urged the US to go to the “dark side” after 9/11. Responding to the Senate report in December 2014, Cheney was even more emphatic, saying he’d “do it again in a minute.” He even accepted that innocents might have been tortured, dismissing this as inevitable collateral damage.

So what happens now? The aftermath of the report’s release has been disheartening at best. In January 2015, incoming Senate Intelligence Committee chair Richard Burr (R-NC) asked the White House to return copies of the full report (only a redacted summary has been released publicly). Sen. Feinstein blasted back, saying this “would limit the ability to learn lessons from this sad chapter in America’s history.” The Obama Administration plans no investigations, let alone prosecutions, of torturers. Although one of the president’s first acts after his inauguration in 2009 was to sign an executive order banning torture, his administration has repeatedly gone to court arguing the state secrecy privilege to prevent victims from pursuing civil claims.

And what of Slahi? He remains one of 122 men still imprisoned at Guantánamo, even though a judge ordered his release and military prosecutors themselves say he’s innocent.

Somehow, throughout this ordeal, Slahi preserved his humanity and even a playful sense of humor. After his lawyer asked him to write about his interrogations, he pointed out that they’ve lasted seven years. “That’s like asking Charlie Sheen how many women he dated.” The portraits of his American guards are especially moving. Despite their frequent cruelty to him, he sees them as complex and often sympathetic.

Rights advocates rightly lambast the White House and Congress for not doing more to investigate and punish torturers. But there will be more and possibly worse stories than Slahi’s. UN rights monitors have called for prosecutions. Already, European lawyers and rights groups are exploring charges against American officials like Cheney, Rumsfeld and others, who will have to beware any Continental vacations.

Even if evidence of torture continues to be buried, one thing is clear. The torture monkey on our back won’t go away anytime soon.