My 12-year-old son has two categories of fear: the specific and the abstract. Sometimes, he jumps when our dog scrambles after the kitten. Night noises, even the winter hiss of a radiator, are scary. So are unexpected knocks at the front door and accidents we pass while driving. All can be named, discussed and fully explained.

Not so with abstract fears. If we are in the car and a radio report on global warming is broadcast, I turn it off. Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth” ranks in my house with “Paranormal Activity” for scare factor. No amount of reasoning (albeit unsatisfying, since all I can really say is “somebody will figure this out” and “remember to recycle and turn out the lights”) dilutes the abstract fear.

“Why does global warming scare you so much,” I once asked my son, after silencing the smooth voice of a host on “All Things Considered.”

“Because when I grow up, there will be no world for me to live in.”

That he is wrong, but also terrifyingly right left me without a soothing comeback.

Adults have the experience and perspective to acknowledge abstract fear and deal with it (albeit often with willful ignorance). A disaster strikes, but I am safe in my home; I fall on a rollercoaster without really falling; and viewing a film about the death of a child (think “Ordinary People” or the more recent “Rabbit Hole”) provokes strong emotion that eases over a post-screening glass of wine.

For children, though, dealing with these questions can be conceptually world-ending. Why do people destroy our environment? How can people war over color or language? Who are the extremists that think it right to oppress or kill others? What motivates one group to exterminate another and consider it just?

When I began drafting my young adult novel, this was precisely the ground I intended to mine. Inspired by books like The Book Thief (Marcus Zusak, Alfred A. Knopf), “The Hunger Games” series (Susan Collins, Scholastic) and Phillip Pullman’s “His Dark Materials” series (Alfred A. Knopf), I wanted to explore how a group convinces itself that genocide is a moral act, ridding a world of a threat. Though my human rights work, I see this thinking lurking within most genocides, from the slaughter of the Armenians (termed “bandits” by the Ottoman masterminds) to the Holocaust, Cambodia and Guatemala. I chose to write a dystopia that would bring teen readers inside the logic of mass killing to see through plot and sympathetic characters how atrocity can be perpetrated for seemingly noble reasons. The genocidaires, as they are known in Rwanda, are not essentially evil, but rather normal people who are transported by evil ideologies.

A surge in dystopian fiction is testament to a vibrant subgenre that puts such questions about human society directly to young adults. Of course, dystopias are nothing new to children’s literature. As Laura Miller pointed out in a recent issue of The New Yorker, “Readers of a certain age may remember having their young minds blown by William Sleator’s House of Stairs, the story of five teen-agers imprisoned in a seemingly infinite M. C. Escher-style network of staircases that ultimately turns out to be a gigantic Skinner box designed to condition their behavior. John Christopher’s The White Mountains, in which alien overlords install mind-control caps on the heads of all those over the age of thirteen, tore through my own sixth-grade classroom like a wicked strain of the flu. Depending on the anxieties and preoccupations of its time, a dystopian Y.A. novel might speculate about the aftermath of nuclear war (Robert C. O’Brien’s Z for Zachariah) or the drawbacks of engineering a too harmonious social order (Lois Lowry’s The Giver) or the consequences of resource exhaustion (Saci Lloyd’s The Carbon Diaries 2015).”

Today, dystopias make up a significant portion of the young adult market. As of February 2011, The Book Thief has been on the paperback bestseller list for an astonishing 177 weeks  (in contrast, the seven-book “Harry Potter” series has been on the list for 244 weeks). “The Hunger Games” series is climbing at 23 weeks and will soon be a movie. Pullman’s “His Dark Materials” series, inspired by John Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” among other things, has been adapted for radio, the stage and film, and has provoked a dramatic reaction from the Catholic Church (organized religion is the villain, angels are both good and bad and Satan is a hero).

(in contrast, the seven-book “Harry Potter” series has been on the list for 244 weeks). “The Hunger Games” series is climbing at 23 weeks and will soon be a movie. Pullman’s “His Dark Materials” series, inspired by John Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” among other things, has been adapted for radio, the stage and film, and has provoked a dramatic reaction from the Catholic Church (organized religion is the villain, angels are both good and bad and Satan is a hero).

If anyone doubts the vibrance of the genre, check out what happened when BitchMedia posted a list of 100 Young Adult Books for the Feminist Reader, then started excising books from its list after readers complained. Among others, author Scott Westerfeld, whose “Uglies” series explores the dark side of the quest for beauty, was among those engaged in a flame war opposing censorship around difficult issues, like rape.

I’ve found that dystopias are fun to craft, since the author is master of the universe in ways realist fiction does not allow. As long as I am true to plot and character, fuel in my story can come from a mysterious Cyclon and children can have the ears of rabbits. But what remains immutable is human nature, which emerges through fantasy and alien universes in surprising, powerful ways.

Some critics, including Miller, bring an edge of derision to their critique, contending that dystopias are “not about persuading the reader to stop something terrible from happening—it’s about what’s happening, right this minute, in the stormy psyche of the adolescent reader.” Dystopia is reduced to high school, in other words.

I believe this view sells short author and reader. While many dystopias can be interpreted through the lens of allegory, for me that is only a beginning. Writers like Zusak, Collins and Pullman are after much bigger game. The Book Thief makes Death the narrator, both fascinated and frightened by the human capacity for good and evil, as seen through the life of a German girl growing up during the Holocaust. “The Hunger Games” series examines how elites oppress and divide minorities through propaganda and entertainment. Pullman’s series, beginning with The Golden Compass (US edition), questions organized religion and makes a value out of individual freedom over institutions.

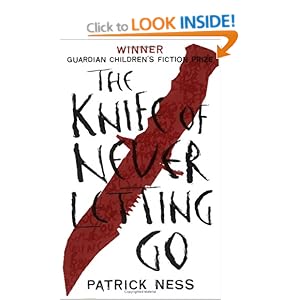

All of these struggles are as visible to children as the daily news. Yet they often go unremarked by adults or, at best, shrugged away. Children ask, with fresh amazement, how we, their elders, can tolerate such injustice and destruction. As advances in  technology shape the world, dystopias also give their readers a way to explore them, from the constant presence of advertising (Feed, M.T. Anderson) to the insanity of voracious colonization (The Knife of Never Letting Go, Patrick Ness).

technology shape the world, dystopias also give their readers a way to explore them, from the constant presence of advertising (Feed, M.T. Anderson) to the insanity of voracious colonization (The Knife of Never Letting Go, Patrick Ness).

The questions dystopias pose are not necessarily new, though the worlds often are. Some critics resist including “real-life” dystopias in this category. But the world of The Book Thief, for instance, is as strange to young readers as any off-earth construct. The book examines the mechanism that makes people capable of killing others solely because they are members of a certain group, in this case Jews.

Interviewed about his inspiration, Zusak recounts a story told to him by his German mother. As a child, she heard noises one day and watched Jews being rounded up like cattle. A teen-aged neighbor gave an old man a piece of bread. The man fell to his knees and embraced the boy’s ankles. But a soldier grabbed the bread and whipped both the Jew and the boy. “On one hand you have pure beauty, which is the boy giving the bread,” Zusak says. “On the other, you ‘ve got pure destruction, which is the soldier doing what he did. Bring those things together and you’ve got humans.”

In The Hunger Games, heroine Katniss Everdeen selflessly volunteers to be a “tribute” and participate in the annual hunger games, a gladiator-style fight to the death that pits equally poor communities against one another for the prize of a bit more food and entertainment for the capital’s elites. At issue here is our fascination with watching those less fortunate than ourselves (think Jerry Springer or Jersey Shore), especially when they are forced to behave like animals – then become heart-breakingly human. The books also take readers inside the mechanisms of propaganda and manipulation, and how resistance can subvert these powerful tools of control. There’s an interesting interview with the author about her thinking on war here.

At the core of dystopias is a very human question: how people really behave. Especially as teenagers, children are beginning to see that the world is not all that has been promised. The best dystopias ask the essential questions: Why is this so? Does it need to be so? And who says this must be so? Through dystopias, children can begin to experience what it means to be human in the twenty-first century, with all the despair – and hope – that this implies.