Images of Belfast’s brick-hurling thugs seem like unwelcome eruptions of ancient history on our Internet feeds. Rooted in England’s very first colonial venture under Henry II in the 1100s, the continuing argument over Northern Ireland is both impenetrable to outsiders and embarrassing to most natives, who spend their summers dodging riots, eyes stinging from smoke belched by towering bonfires.

Even writing about Northern Ireland is filled with roadblocks. It’s Protestants vs. Catholics, except faith is really beside the point; Loyalists vs. Republicans, though most Northern Irish identify as neither and want nothing to do with violence; or Unionists vs. Nationalists, except a growing number of Catholics support remaining with the United Kingdom and thousands of Protestants have voted with their feet by leaving the island entirely.

Some dispute that the English colonized Ireland at all, since Henry’s troops were actually invited in by a desperate Irish nobleman who then watched the monarch swallow the island whole.

Why haven’t these people gotten over it yet, Americans might ask? And why exactly should we care?

A Chicago native with Ulster roots, I’ve watched for years as the Journeyman Plumbers dump orange powder into the Chicago River on St. Patrick’s Day,

dying the murky water a virulent green. Billed as a spectator-friendly celebration, in fact it’s a Catholic/Nationalist/Republican insult to any member of the Protestant/Unionist/Loyalist faithful, who call themselves Orangemen after King William of Orange (another acquisitive European monarch).

The quick answer is that the past always matters, everywhere. On the streets of Belfast, the Northern Irish are giving us a master class in its potency. What is less heralded is that in this tiny, lovely corner of the old sod, people are also acknowledging the past and finding creative, effective ways to drain it of hatred.

Maybe it doesn’t look that way in July and August, so-called “marching season,” when Orangemen pound their war-like Lambeg drums along Catholic streets. Aggrieved Catholics respond with their own shouts, sometimes leading to exchanges of bricks and petrol bombs.

But for most of the year, there’s a lesson here that Americans would do well to learn.

Why? Our own past bites at us with alarming frequency, whether it is through New York City’s racist stop-and-frisk laws or the wing-nut insistence that our president is a Muslim, Kenyan or both. In North Carolina, where I live, the governor just signed a voter ID law that reads like a primer on how to disenfranchise African Americans and the poor, Jim Crow-style. When I protested the bill (and was arrested) at the state legislature in June, accompanying me was 92-year-old Rosenell Eaton, an African-American woman who, unlike any whites, had to recite the preamble to the US Constitution perfectly just in order to vote (and she succeeded).

Yet white America in particular denies or just doesn’t see that racism is alive and even thriving. A recent Daily Show episode highlighted the gap with separate white and black focus groups (questioned by correspondents Jessica Williams and Samantha Bee). Whites thought racism was largely a thing of the past; the grim faces of the black guests, failing to see much humor in Bee’s theatrically sweat-soaked blouse, signaled a very different view.

Four of the five African Americans had been stopped by police in New York (the one hold-out had just moved there). Only one of the whites had been searched — as it turns out, with thousands of other passengers in an airport security line.

I’ve been bringing Duke students to Northern Ireland since 2009, a decade after the Troubles officially ended with a peace agreement. The students volunteer with groups working toward peace. In the city, the walls between communities are concrete and chain-link, not lodged in the color of our skins as they are States-side. Over 90 percent of Northern Irish K-12 students still attend segregated schools. Most people live in self-segregated neighborhoods, mixing only downtown or when an international act books in at the Odyssey. Even favored vacation spots in Spain and Portugal are divvied up by tribe.

So what, exactly, could the Northern Irish possibly be doing right? Most importantly, not a soul on the island denies that history shapes the present and matters. History matters a lot. People talk about history constantly — on talk radio, in pubs, around the kitchen table. Institutions like the church, the government and international funders engage in and support efforts to bridge communities divided by the past. Quietly, people marry across the divide, work in mixed offices, club in mixed groups and play on mixed teams. At kindergarten pickups, birthday parties and graduations, formerly warring tribes find new bonds that build on, but aren’t split by, the past.

For the first time this summer, Northern Ireland’s leaders proposed a plan to disassemble walls first erected in the 1960s, to dampen cross community attacks. The plan remains aspirational, but it’s something everyone discusses, a healthy sign. Amnesty International recently released a report showing how much work needs still to be done. Yet there are people and groups who have already dedicated themselves to this necessary work, a positive sign.

Discussion, in the end, is the first step to addressing the past. But to discuss, you have to first admit that there is a problem. That’s where Americans fail. Americans Paul van Zyl, who worked on South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, said it best: “It’s not whether you will confront the past. You will. The question is on whose terms.”

President Obama doesn’t support a White House forum to discuss our history of racism, and I agree. These sorts of discussions work best closer to home, when people know each other as neighbors and colleagues. Instead, the president should propose a plan to encourage American cities and towns to hold their own fora, with the power to take action, whether it is to devise ways to address racism, recognize forgotten heroes or simply come together to celebrate.

Whites who don’t see a problem need to step back and listen hard. Blacks who claim nothing has changed need to review. No one is exempt from the past; but no one is its prisoner, either.

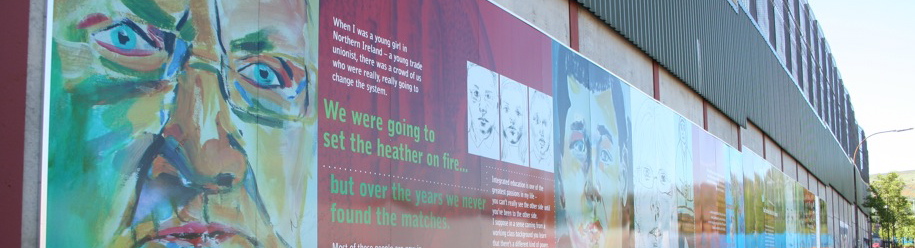

One of my favorite murals in Belfast is topped by a version of a Winston Churchill quote: History is written by the winners. The truth is that each generation writes its own histories, over and over again. There is no single, unifying story, anywhere. We have the power to shape what we do with those stories, though, letting them drive us or turning them to a better use.

In Northern Ireland, people want their histories to lead toward peace and coexistence, in whatever form. Despite the thugs, they are winning. We would do well ask the same of our own stories.

Published in the Belfast Telegraph on September 23, 2013