Reading is not only a powerful tool that connects us to the world and across time, culture, age and gender; it involves a very intimate connection between a writer and a reader. Bernhard Schlink’s The Reader is a novel I often teach, since it allows us to peer inside Germany’s struggle to grapple with the Holocaust and the generations that now know it only as a dark chapter in their parents’ or grandparents’ past.

In it, a boy starts a brief affair with an older woman, Hanna. Many years later he learns that Hanna was a concentration camp guard and took part in the burning alive of Jewish prisoners. Yet he loved her, not knowing of her past.

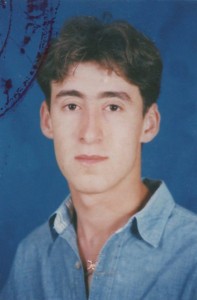

I thought about this book when I read John Grisham’s recent opinion piece about Nabil Hadjarab, a French-Algerian who has been in Guantánamo for 11 years. Hadjarab is a Grisham fan, and had requested the crime writer’s novels only to find out that the prison authorities had banned them for “impermissable content” (one imagines that this may be because Grisham’s forte is showing how the US justice system is deeply flawed, something no Guantánamo prisoner would find the least surprising).

Hadjarab is one of the many prisoners already cleared for release, since there is no evidence he had any connection to Al Qaeda opr violence against the US (he was one of the many foreigners “sold” to the US immediately after the attack on 9/11, for a bounty of $5,000). Subjected to torture and unable to mount a defense, this young man joined the hunger strike and has been force fed, a brutal procedure that is it’s own form of torture.

The Obama Administration says Hadjarab, who was actually raised in France and learned French before Arabic, may be released to Algeria soon. But as Grisham points out, that would be another tragedy:

His nightmare will only continue. He will be homeless. He will have no support to reintegrate him into a society where many will be hostile to a former Gitmo detainee, either on the assumption that he is an extremist or because he refuses to join the extremist opposition to the Algerian government. Instead of showing some guts and admitting they were wrong, the American authorities will whisk him away, dump him on the streets of Algiers and wash their hands.

What should they do? Or what should we do?

First, admit the mistake and make the apology. Second, provide compensation. United States taxpayers have spent $2 million a year for 11 years to keep Nabil at Gitmo; give the guy a few thousand bucks to get on his feet. Third, pressure the French to allow his re-entry.

When you make a mistake, as the United States did in this case, you have to make it right. People like Hadjarab face years of rehabilitation to recover from torture and the deep damage of prolonged and unjust incarceration. France should take him back; and his reentry into free society should be supported by financial support, as with any person wrongfully imprisoned.