This morning, the Summer Institute began with a presentation by Jason Cross on health and human rights. Soon to be a PhD in cultural anthropology, Jason is also a lawyer (Duke Law) and a veteran activist with experience in Europe and Latin America.

He described health as a “gateway” human right and perhaps one of the more radical human rights claims. Unlike civil and political rights, which can be seen as conceptual or having to do with behaviors and ideas, health is rooted in the body, suffering and mortality.

Health can be thought of a “positive” right, he said. Some philosophers and political scientists divide rights into negative and positive. A negative right, for example, is a “don’t mess with me” right. This protects the individual’s freedom without that freedom infringing on the freedom of others. Freedom of speech is one example as are the rights to assembly and due process.

A positive right is a right to something: education, health care, culture. Seen in this way, rights cost money and depend on some entity organizing or providing them, like a government. The negative/positive distinction is not good or bad but frames rights claims in different ways.

“What do people mean when they make human rights claims? What effect do these claims have on the world?” he asked. Jason pointed out that human rights language is relatively new; while people made have made health claims around justice before only post 1950s were these claims phrased in rights language. “As with most languages, things are going to mean different things in different contexts.”

In the American context, how do human rights factor into the debate over health care insurance? No single system is by definition the “rights” option; single payer is no more “rights-y” than government-sponsored (when you pay is different, Jason pointed out, but not how rights-oriented each model can be). Most Americans would say, “If you want health care, work to earn it!” Jason encouraged us not to propose one approach over another, but rather help students understand who different countries and cultures embrace different models as rights-positive.

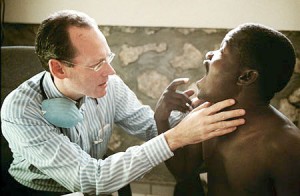

One of the leading thinkers and practitioners in this field is Dr. Paul Farmer, a Duke grad who founded Partners in Health and who has written extensively on this issue. Denying health care when a government can provide it is as lethal as any bullet, Farmer has said.is also a huge ethical question when government impose economic sanctions on other countries that result in higher mortality rates, as with the Iraq sanctions of 10 years ago. Jason emphasized that this challenges us to think about violence differently. he has worked extensively in El Salvador, where human rights activists talk about health as a positive right and link it to issues of dignity.

There is a tension, Jason pointed out, between classic human rights talk and a positive human rights approach. He used the example of how NGOS like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch deal with immigration. They fear “diluting” human rights and getting lost in broader issues that are impossible to measure or quantify. At the same time, groups in countries like El Salvador insist that narrowing everything down to civil and political rights miss the structures that perpetuate abuse, including the economic relationships settled in free trade agreements.

“Part of the struggle is a knowledge struggle and research is important in this regard,” he said.

There are also weirdnesses! Most countries include a constitutional right to health case. Among them is Brazil, here cosmetic surgery is covered by health plans. More helpfully, some countries link populations to clinics, ensuring that there are enough services for their populations. Other countries have used human rights claims to establish cheaper access to certain live-saving drugs, including anti-AIDS and tuberculosis medicines. (South Africa leading the way). Ecuador is currently creating waves issuing its first compulsory license for lopinavir/ritonavir, a key medication in the treatment of HIV/AIDS, circumventing the high cost it would pay on the open market.

While Ecuador has made waves on this, it is not a leader in issuing compulsory licenses, essentially and end-run around patents. That distinction belongs to the US, which issues more compulsory licenses than any other country — most for military technology, not for life-saving drugs.

Finishing up, Jason mentioned two books that are useful in the classroom: Global Health by Mark Nichter and Global Politics of Health by Sara Davies.

An excellent and provocative presentation!