Mexico recently sent a letter to the Spanish king requesting an apology for atrocities committed during the Conquest five centuries ago. Spain quickly dismissed the letter as an attempt to judge the past by modern mores. One outraged pundit wrote, “You cannot judge the events of 500 years ago through the prism of 2019.”

The basis for the request is a Spanish adventurer, funded by the crown, violently toppling the Aztec empire and causing untold thousands of deaths. More lethal were the diseases Hernán Cortes and his men carried, including small pox. Historians speculate that the deadly virus actually burned south ahead of them, felling the Inca emperor Huayna Capac before any European ship landed in modern-day Peru. The Inca’s death touched off a fratricidal struggle that ended with one son killing the other. Spaniard Francisco Pizarro executed the victor in 1533, even though his followers collected huge mounds of gold for ransom.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s letter was not the first sent to a Spanish king to protest the Conquest’s horrors. Even at the time, some judged Spain’s actions publicly and harshly. Critics were a minority, to be sure. Many fortunes were made — and lost — pillaging the region’s riches.

But it’s a mistake for Spain to attempt to elude this request by pretending it is based solely on contemporary mores.

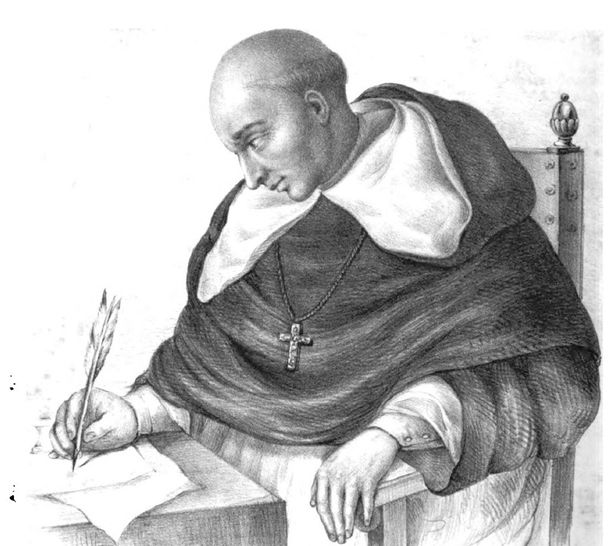

Among the best-known critics was an insider, Spanish priest Bartolomé de Las Casas. Born to a Sevilla merchant family, De las Casas arrived on the island of Hispaniola in 1502, 19 years before Cortés’s victory. De las Casas’s family owned land on the island and with it the indigenous people living there.

De las Casas witnessed atrocities first-hand, including massacres and the brutal treatment of people forced to mine for coveted gold. By 1515, he was penning pleas to Spain to avoid violence and enslavement. He was by no means “woke.” Reflecting widespread acceptance of slavery, he for a time advocated importing African laborers, considered hardier then natives. But he eventually abandoned that idea, arguing that all slavery be abolished.

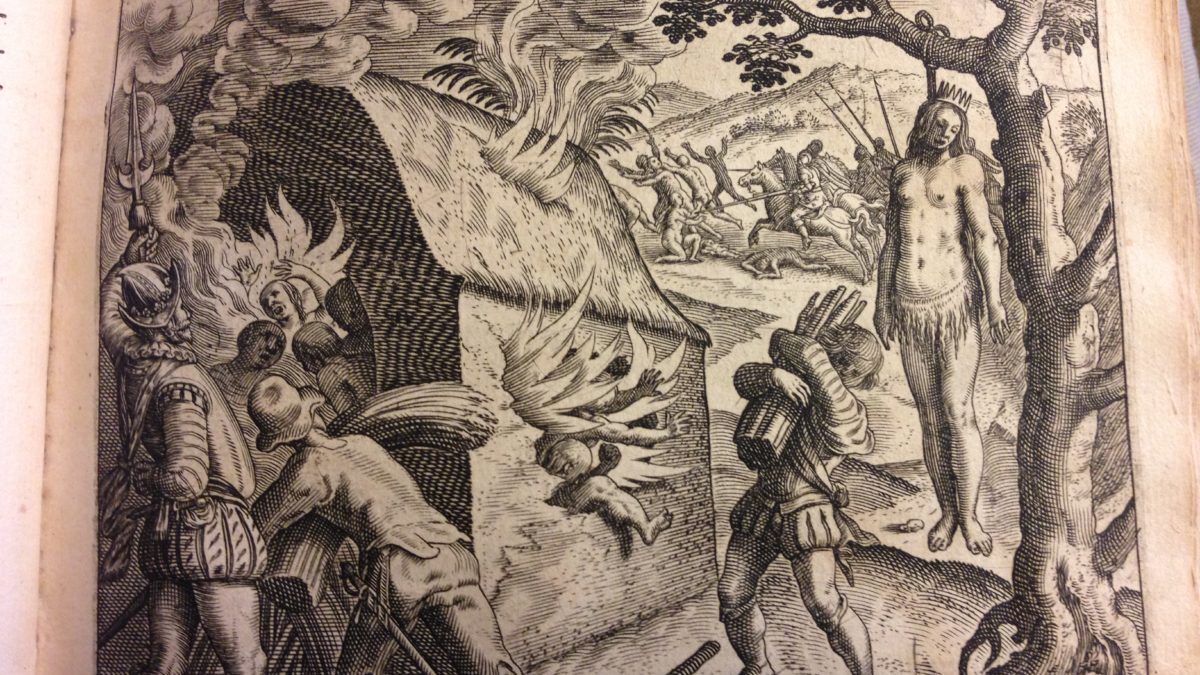

Among his many works, De las Casas’s “In Defense of the Indians” stands out. In it, De las Casas chronicles horrors that read eerily like modern human rights reports. He shows an advocate’s ear for the most compelling examples of evil. In one passage, De las Casas recounts how conquistadores targeted women and children, snatching “young Babes from the Mothers Breasts, and then dasht out the brains of those innocents against the Rocks; others they cast into Rivers scoffing and jeering them, and call’d upon their Bodies when falling with derision, the true testimony of their Cruelty, to come to them, and inhumanely exposing others to their Merciless Swords, together with the Mothers that gave them Life.”

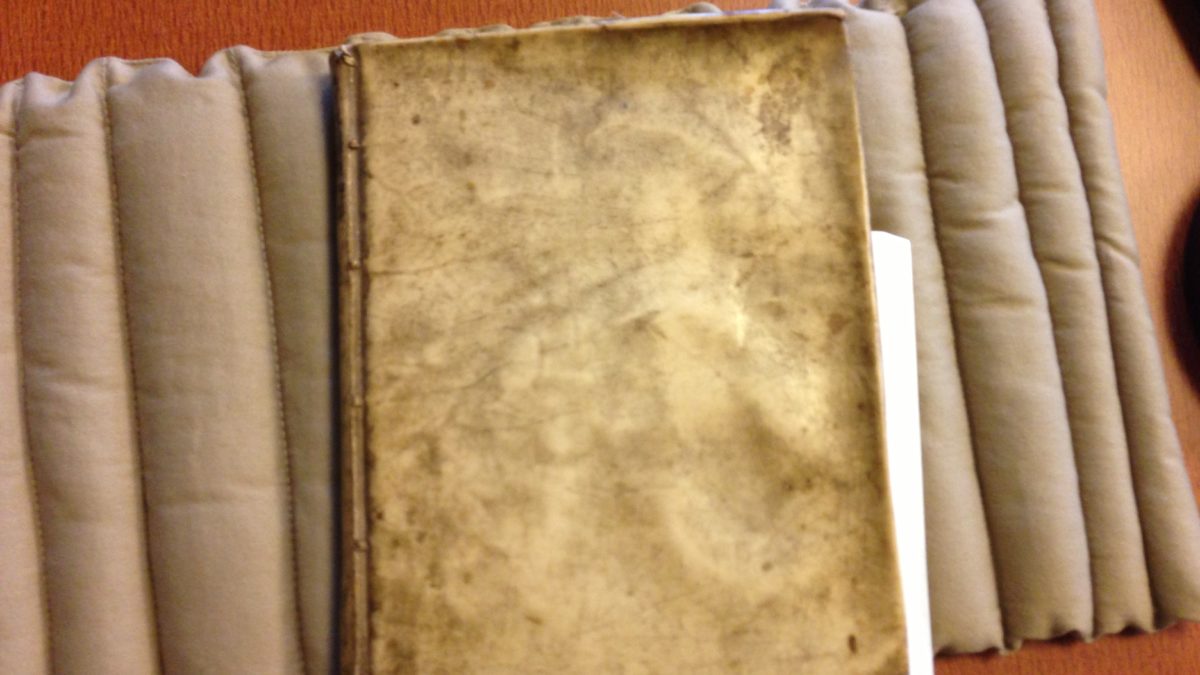

The images below are of a 1698 edition of De las Casas’ Relation des Voyages et des Découvertes que les Espagnols ont fait dans les Indes Occidentales, bound in bone and in Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library

These appeals won mild reforms. One papal bull, Sublimis Deus, proclaimed that natives were human and should not be enslaved or robbed. In 1542, Spain promulgated laws abolishing slavery and the plantation (encomienda)system, with decidedly mixed results.

Another letter writer, Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala, was a native, born just after Pizarro’s victory over the Inca. He likely learned Spanish from priests and officials. For some reason, Guamán Poma was banished from his home province, and he embarked upon a journey through a Peru still torn by violent occupation.

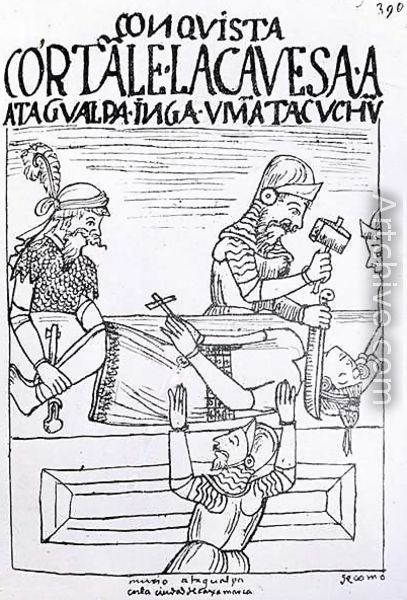

It was then that Guamán Poma — the Quechua translation is “Falcon Cougar” — began writing what came to be “The First New Chronicle and Good Government,” a 1,189-page letter that includes 398 full-page line drawings. Meant for King Philip III, the text is in Spanish with some Quechua. Much of the letter is Guamán Poma’s account of Inca history and customs, to support his central argument. He didn’t argue for reform of the Conquest. He argued powerfully that the Conquest itself was wrong and that Spain should withdraw and treat Peru as an equal.

When I teach these two authors in my human rights classes, I point out how they can be seen within an age-old debate over how to best pursue change. Are you a reformist who advocates, like De las Casas, for gradual change? That strategy was later adopted by anti-slave trade campaigners as well as modern-day death penalty abolitionists, who chip away at abuses over many decades.

Or are you, like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, unwilling to wait any longer? Reading “The Letter from the Birmingham Jail” along with Guamán Poma’s Chronicle underscores the stark difference between how allies and how victims of abuses can approach change.

In the book, Guamán Poma depicts himself presenting his masterpiece to the king. Sadly, there’s no evidence the king ever received it. The stack of yellowed, cracked pages was only rediscovered in a European archive in 1908. Perhaps some noble promised the earnest Peruvian that they would personally deliver his life’s work. Likely, it was sold and resold as an oddity.

You may side with Guamán Poma’s passionate rejection of the Conquest, but De las Casas — a Spaniard, priest and white man — had more positive impact on curbing abuses. On the other hand, the priest’s advocacy of gradual change left the deep and persistent scars President López Obrador wants Spain to acknowledge.

During a visit to Madrid several years ago, I eagerly raced through the magnificent Museo Del Prado to see how this grand culture viewed its Latin American brethren. I left disappointed. I located a single painting, some Spanish nobleman surveying a Panamanian inlet. Even as Latin America looks to Spain as a touchstone, Spain’s gaze seemed to be to Europe or inward, to its own tangled history.

When I conveyed my disappointment to a Peruvian friend, he snorted, “We were there. You were looking in the wrong place.”

Had I missed a room? An exhibition?

“What color were the frames?” he asked.

“Gold,” I answered.

“And where do you think they got that gold?”

Of course, the mound collected in return for the Inca’s life. Remorseless, Pizarro slit his throat and sent the spoils to Spain.

Whether we acknowledge it or not, the past frames our present and shapes the future. The Conquest’s scars will never go away. But by apologizing, Spain can help reframe its relationship to Mexico and the rest of Latin America for the better.

Maybe the spirit of Guamán Poma’s letter will finally help convince the Spanish king.