This post first appeared in Fantasy Cafe

Map-makers have always drawn with their imaginations even when they thought they were making factual representations. Recently, I came across this detailed depiction of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec empire’s capital, published anonymously on Nuremberg in 1524 and featured in Elizabeth Hill Boone ’s The Aztec World. Some elements are somewhat accurate. The city was built on an island. Commerce on the pictured road was robust as tribute poured in from subjugated communities. As Boone writes, one Spaniard noted of the actual city how “everything was whitened and polished, indeed the whole place was so clean that there was not a straw of a grain of dust to be found there.”

But what of the round cylinders toward the base? How is the small, lake-like body of water to the left connected to the city? To some extent, all maps include some level of the imaginary (if only because the planet and the people on it are always moving). Maps include more than location and building style. For instance, at the upper right of the Nuremberg map, the distinctive coat of arms of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of much of modern-day Europe, waves over a depiction of the conqueror’s castle. This is history, Spain’s bloody takeover not more than three years earlier.

The Latin inscriptions tell another tale. Not only was this the language of European officialdom. The Catholic Church supported adventurers like Hernán Cortés, who toppled the empire, and forcibly and sometimes murderously converted the indigenous population, at first more interested in numbers than the survival of new adherents. The map itself communicates power and control. Many scholars argue that the act of drawing maps of subjugated peoples and continents has been a part of building empire.

Fantasy maps turn real-world cartography on its ear. Instead of using real places to spin fantasy, fantasy maps use the format and conventions of actual maps to build imagined worlds. Whether the maps are street-level depictions or include whole continents, fantasy maps parlay our assumptions and relationships with maps into delightful imagined worlds. Like the Spanish map of Tenochtitlán, they also can serve as a powerful story-telling tool, showing us the central conflicts of the stories we love.

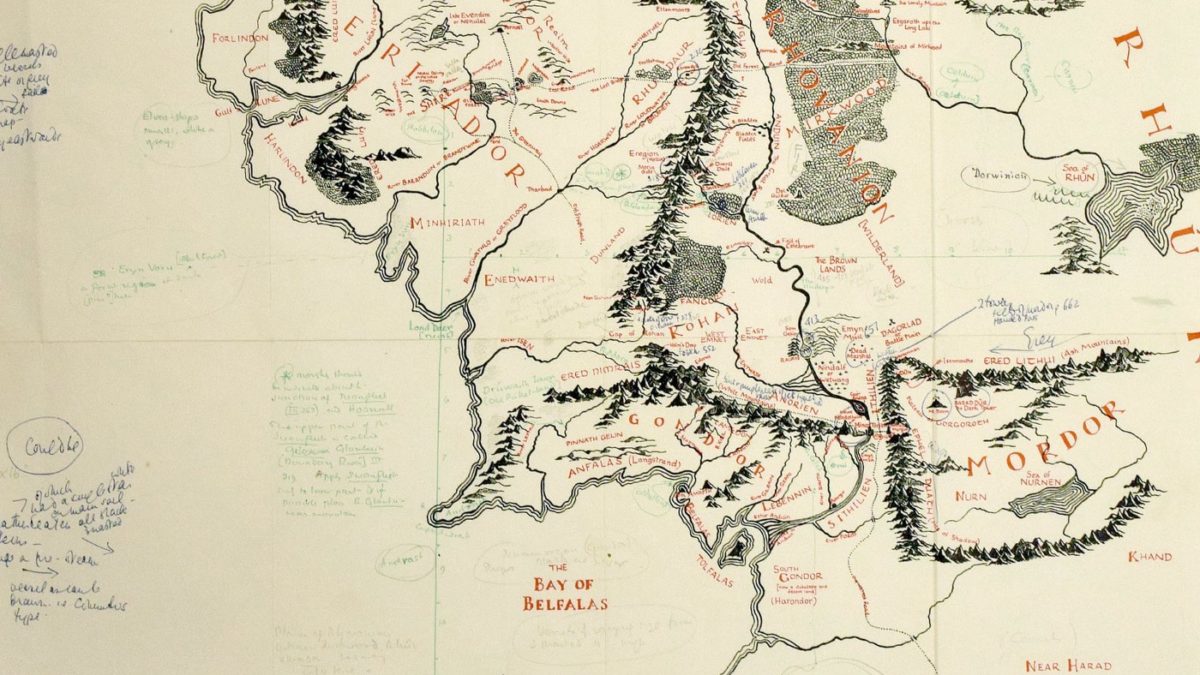

Like many, I got my first introduction to fantasy maps from J. R. R. Tolkien. As he wrote, for him, the map was not an extra, but a first step in story-telling, since “in such a story one … must first make a map and make the narrative agree.” His youngest son, Christopher, drew the map included in the 1954 publication of the first two volumes of The Lord of the Rings. Recently, Tolkien’s own annotated version of the map resurfaced, prepared for illustrator Pauline Baynes for the 1969 poster of Middle-earth.

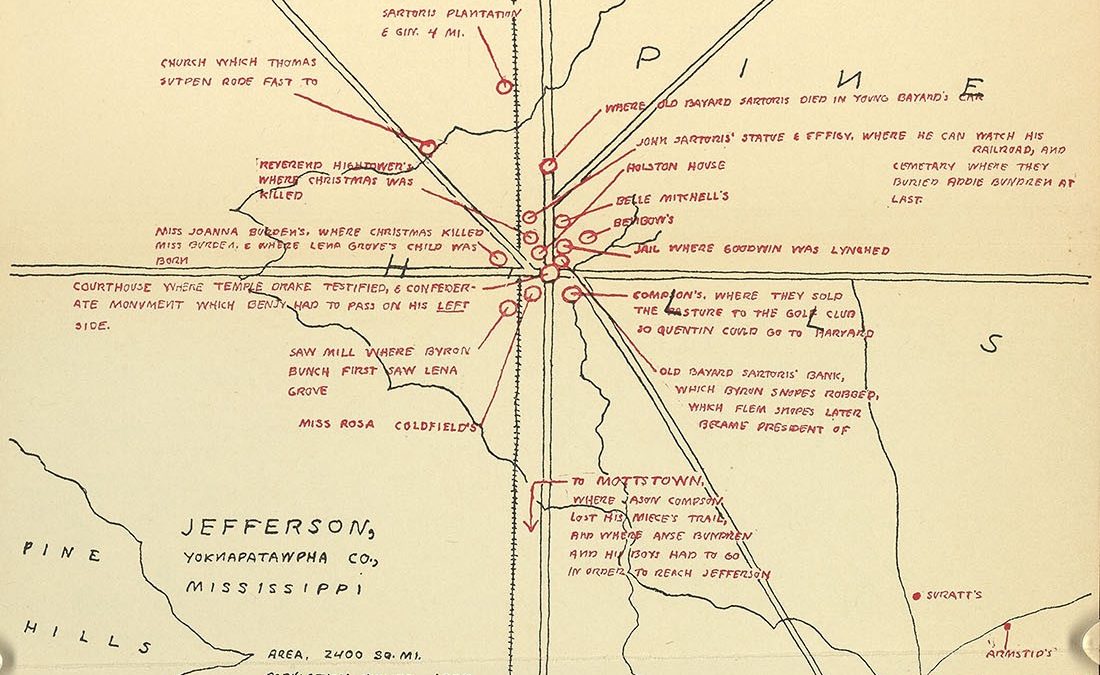

In his gorgeous The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, Huw Lewis-Jones mixes real-life maps with imaginary ones: Philip Pullman’s Eschtenburg from The Tin Princess, Anthony Trollope’s Barsetshire, William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, among others. Clearly, not all belong to completely fantastical realms. But Faulkner seemed just as insistent on his map as Tolkien, scribbling on one draft, “Surveyed & mapped for this volume by William Faulkner.”

In his gorgeous The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, Huw Lewis-Jones mixes real-life maps with imaginary ones: Philip Pullman’s Eschtenburg from The Tin Princess, Anthony Trollope’s Barsetshire, William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, among others. Clearly, not all belong to completely fantastical realms. But Faulkner seemed just as insistent on his map as Tolkien, scribbling on one draft, “Surveyed & mapped for this volume by William Faulkner.”

Library, Charlottesville, Va.

There’s a lovely practicality to black-and-white maps and an exuberance to color maps, including maps made to accompany comic books. Maps were so important to science fiction that Dell published “map-backs” in the late 1940s, each book featuring a color map on the back. Lewis-Jones highlights their playful, interactive appeal as “invitations. We can read them, draw and redraw them, use them share them, add and alter them, enter into them. As representations, they are always partial, always incomplete, and yet they always offer us more than what is held there on paper alone.”

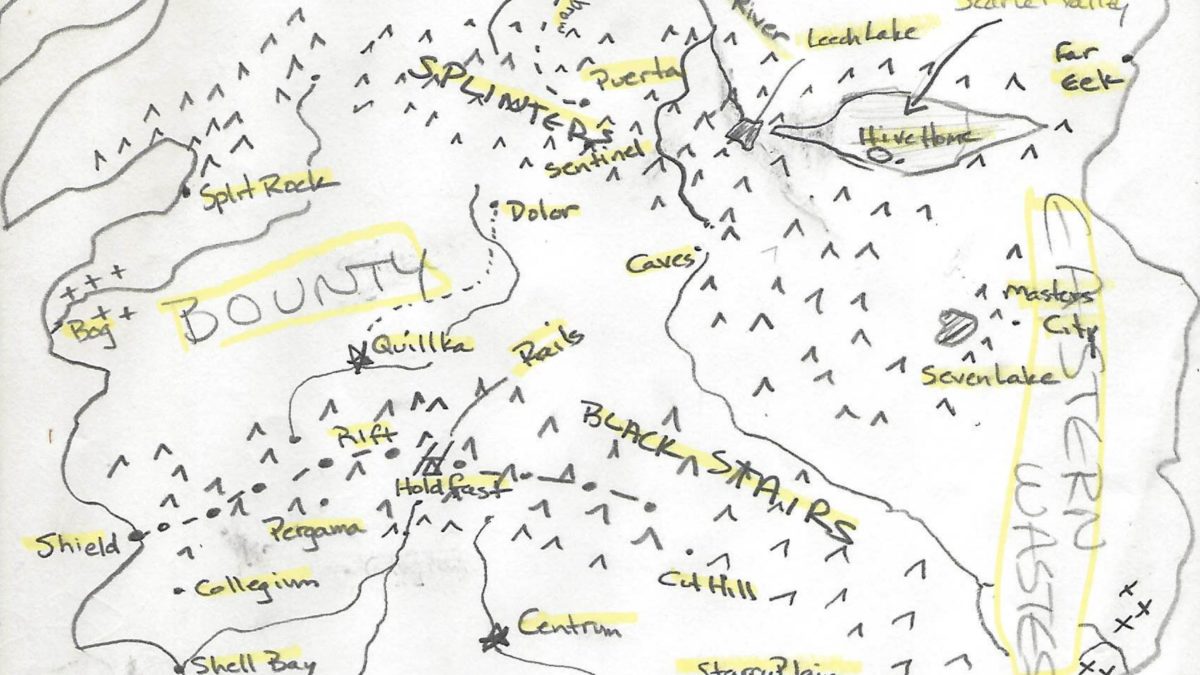

When I wrote The Bond, the first book in my YA fantasy trilogy, I had a rough idea of the landscape in my head. I love California’s Trinity Alps, my inspiration for the Black Stairs. I lived in Peru and experienced many a breathless (and terrified) moment crossing the Andes. Mountains had to be a part of the story.

But I also loved the wet denseness of the jungle, the crisp clarity of the puna, the high mountain desert. Perhaps a bit like Tolkien, I realized I had to draw a map if I was ever to write an intelligible story.

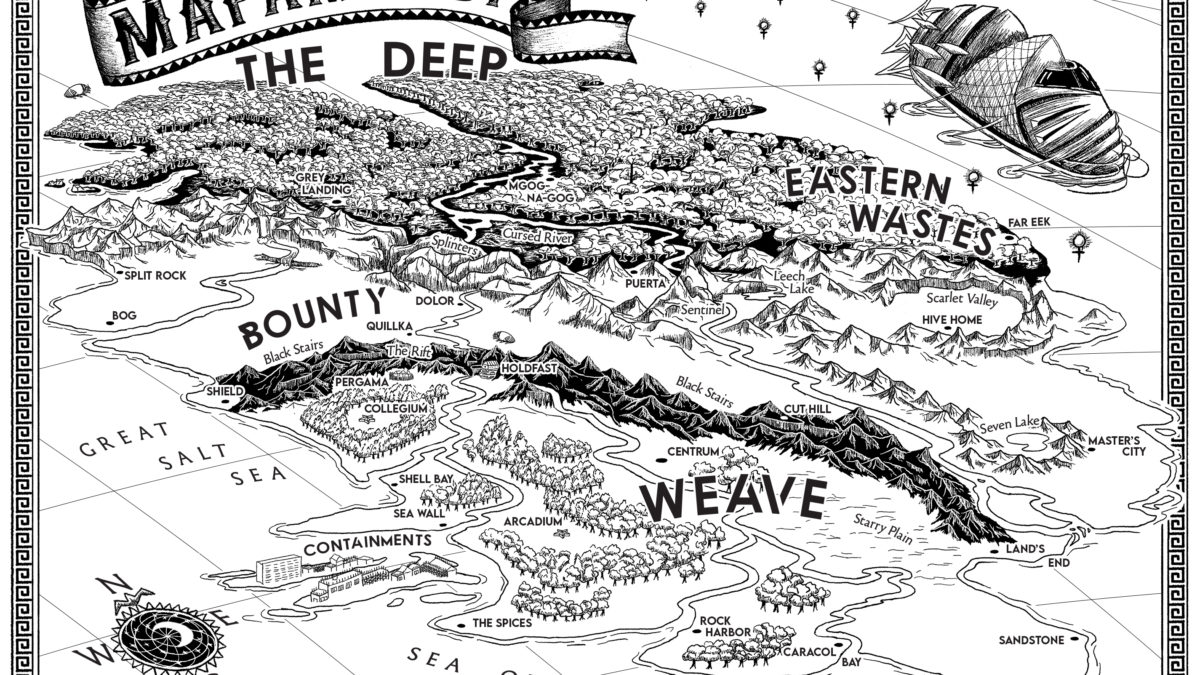

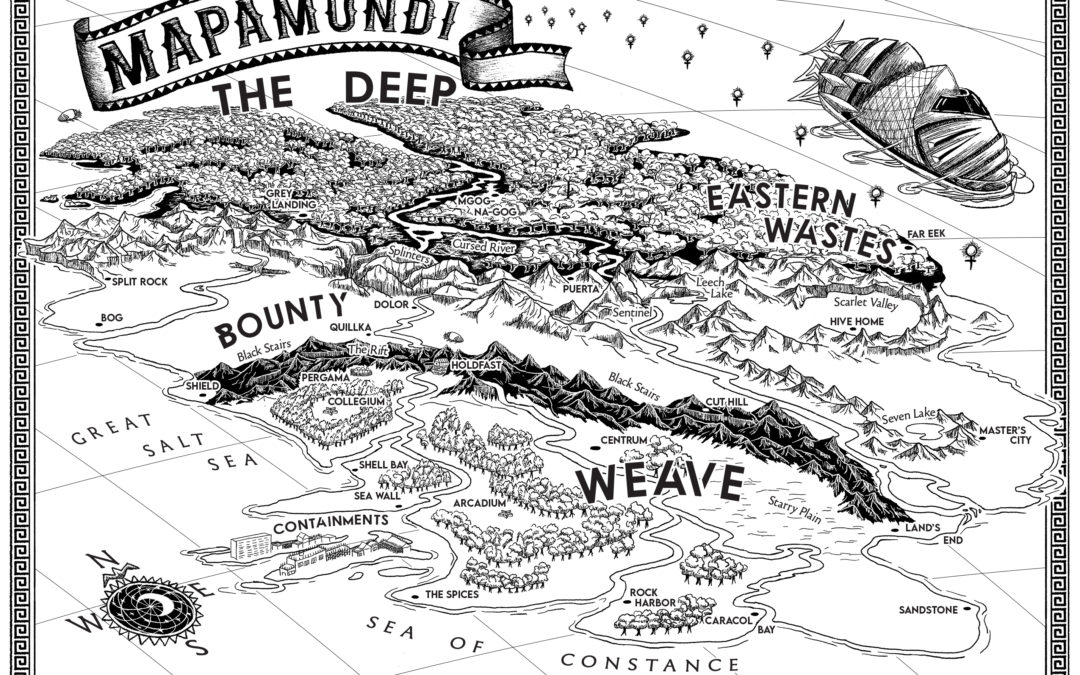

The first versions were for me alone. My questions were practical. If my main character was headed north, how far until she reached a plain? With Book II, The Hive Queen, I opened up a whole new area, the Eastern Wastes. There were rivers to cross, hidden valleys to traverse, strange cities to discover.

About mid-way through the revision of The Hive Queen, I realized readers, too, might appreciate a map. I was lucky enough to find a wunderkind map-maker to work with. I could tell by Travis Hasenour’s maps that he was precisely the artist I wanted (here’s his online portfolio). Each of his maps is different, each wonderfully calibrated to story, and all reveal a deep respect for the author’s world along with an inventiveness that I could never match.

I sent him my best guess at a map. Even the act of drawing it sent me running back to the text, to adjust a mountain range or the curve of a river.

When Travis sent a first draft of his interpretation, I had to sit down to catch my breath. It was … spectacular. Once, a young reader came up to me to ask a question about one of my characters and I felt the equivalent of a gut punch. How did she know this character? I wondered crazily. Characters take up spaces in writers’ brains, and then they walk — or leap or dance — into the heads of readers just as if they were real.

The way maps work is eerily, magically similar. When Travis sent me the final version of The Bond’s Mapamundi, it was as if I experienced a dozen good birthdays and holidays together. And cheesecake. I’ve written a world into existence and now, through the power of words and a map, it exists.

There’s no more reachable magic than this. Travis included so many lovely details — the whispered ships traveling the Signal Way, the star-shaped schools, the stylish compass rose. Though I wrote the story, it’s more real to me when I gaze at this marvelous map.

I’m doing a “map reveal” here, in advance of The Hive Queen’s August release. I hope you enjoy it — and come back for the story!